As with many great ideas, this one arose during an offsite meal during regular conference hours. In brief, I was talking with a former grad student now assistant professor about how to help preservice teachers learn to generate great lesson plans in short order. If my memory is accurate, I was probably lamenting (another common precursor to brilliant advances) how in the spring after I taught them science teaching methods in summer, many of my science teaching candidates forget all that they learned. This all comes to a head when one of them is invited to teach a lesson as part of the job interview process. They panic and send me drafts of their lesson. These are so bad, that I have used them as counter-examples in subsequent courses.

I suspect future teachers come to their preparation program with preconceived notions about teaching-as-performance. What else would explain why a middle school candidate, when told to do a lesson on magnets, included in her plan a video of a frog suspended in a magnetic field. Luckily, even via email, I was successful with having my former student recognize the folly of her plan. And in sharing this story, my crepe-munching companion suggested that I should train them to prepare lessons as if they were on the Amazing Race. If you aren't familiar, the signature moment is when the competitors tear open an envelope to learn their next challenge. What if instead of rushing off to eat live octopus or find objects in a rat-filled building, the competitors had to develop a winning lesson plan?!

Luckily, even via email, I was successful with having my former student recognize the folly of her plan. And in sharing this story, my crepe-munching companion suggested that I should train them to prepare lessons as if they were on the Amazing Race. If you aren't familiar, the signature moment is when the competitors tear open an envelope to learn their next challenge. What if instead of rushing off to eat live octopus or find objects in a rat-filled building, the competitors had to develop a winning lesson plan?!

Many of my teaching strategies are designed to help manage my own petty frustrations. For example, I thought it unfair that a student could earn all the points in a class to earn an A and have poor attendance. Rather than become perturbed, I created a policy whereby I would calculate a final grade based upon the lower of two percentages: points earned or attendance rate. No-shows didn't trouble me at all because it had the potential for influence their GPA. I also felt as if that policy reduced absences. Fast forward to 2011 where I'm irritable that all the best instructional strategies we discuss and rehearse are put in a box and shoved under the bed once a teaching interview arises. This summer, I have been emphasized the Grand Unified Lesson Plan (GULP) as the lesson framework:

on a whim I proposed that this was much like "Iron Chef." You know in advance that you have to prepare a multi-course meal. You must have the necessary preparatory and plating skills along with some creativity. It isn't until the secret ingredient is revealed ("Frozen PEAS!!") that you are able to channel your skills and expertise toward a product. Several students nominated this analogy as valuable in their weekly electronic reflections. And so the trap has been set for the last class session.

on a whim I proposed that this was much like "Iron Chef." You know in advance that you have to prepare a multi-course meal. You must have the necessary preparatory and plating skills along with some creativity. It isn't until the secret ingredient is revealed ("Frozen PEAS!!") that you are able to channel your skills and expertise toward a product. Several students nominated this analogy as valuable in their weekly electronic reflections. And so the trap has been set for the last class session.

On that morning, students will be divided into four person teams representing a cross-section of science certification areas. After a few preliminary bits of foolishness (e.g., "what element is sung immediately before and which is sung immediately after the element whose symbol is Sn?") the troops will receive the topic that is to be the focus of their lesson plan. They are to create an entire GULP format lesson based upon this supplied term. They are to also employ accommodations for English language learners and make sensible use of an educational technology. Actually, we may have to scratch the latter because it feels unrealistic. But in many ways it simulates what should transpire in the days and hours leading up to delivering a sample lesson to a roomful of strangers. Furthermore, it forces the participants to engage in debates about instructional design. Ideally, it will also induce them to engage in the spirit of collaboration that we believe is so central to the profession yet rarely demonstrated -- let alone practiced.

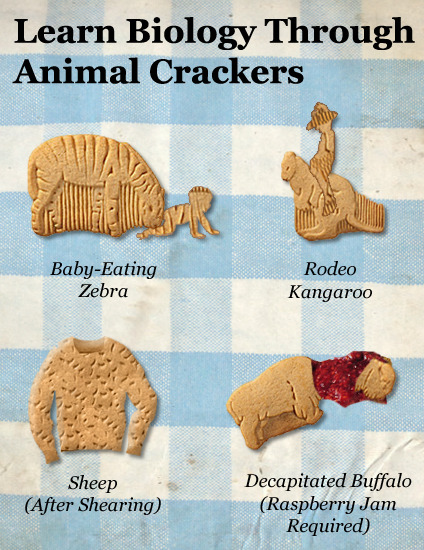

And that is our plan for now. Otherwise, I'm working on concepts that would be useful whether a person has allegiance to biology, chemistry or physics and have some evidence of a variety of student misconceptions. Currently, those topics are Oxygen, Energy Transformations and Conservation of Mass. Admittedly, it's not as clever as turning sheep fuzz into footwear. But at least I won't have to imagine how it all comes together.

I suspect future teachers come to their preparation program with preconceived notions about teaching-as-performance. What else would explain why a middle school candidate, when told to do a lesson on magnets, included in her plan a video of a frog suspended in a magnetic field.

Luckily, even via email, I was successful with having my former student recognize the folly of her plan. And in sharing this story, my crepe-munching companion suggested that I should train them to prepare lessons as if they were on the Amazing Race. If you aren't familiar, the signature moment is when the competitors tear open an envelope to learn their next challenge. What if instead of rushing off to eat live octopus or find objects in a rat-filled building, the competitors had to develop a winning lesson plan?!

Luckily, even via email, I was successful with having my former student recognize the folly of her plan. And in sharing this story, my crepe-munching companion suggested that I should train them to prepare lessons as if they were on the Amazing Race. If you aren't familiar, the signature moment is when the competitors tear open an envelope to learn their next challenge. What if instead of rushing off to eat live octopus or find objects in a rat-filled building, the competitors had to develop a winning lesson plan?!Many of my teaching strategies are designed to help manage my own petty frustrations. For example, I thought it unfair that a student could earn all the points in a class to earn an A and have poor attendance. Rather than become perturbed, I created a policy whereby I would calculate a final grade based upon the lower of two percentages: points earned or attendance rate. No-shows didn't trouble me at all because it had the potential for influence their GPA. I also felt as if that policy reduced absences. Fast forward to 2011 where I'm irritable that all the best instructional strategies we discuss and rehearse are put in a box and shoved under the bed once a teaching interview arises. This summer, I have been emphasized the Grand Unified Lesson Plan (GULP) as the lesson framework:

In an effort to reinforce this framework and the associated expectation,Step 0. Identify topic and Translate into Big Idea

Step 1. Pre-assess Every Student

Step 2. Engage: Build Public Representation

Step 3. Explore: Small group activity

Step 4. Explain: Combing Findings with Teacher Input

Step 5. Access Scientific Information: Quick Read

Step 6. Extend: Application Discussion

Step 7. Evaluate: Closure / Exit Slips

on a whim I proposed that this was much like "Iron Chef." You know in advance that you have to prepare a multi-course meal. You must have the necessary preparatory and plating skills along with some creativity. It isn't until the secret ingredient is revealed ("Frozen PEAS!!") that you are able to channel your skills and expertise toward a product. Several students nominated this analogy as valuable in their weekly electronic reflections. And so the trap has been set for the last class session.

on a whim I proposed that this was much like "Iron Chef." You know in advance that you have to prepare a multi-course meal. You must have the necessary preparatory and plating skills along with some creativity. It isn't until the secret ingredient is revealed ("Frozen PEAS!!") that you are able to channel your skills and expertise toward a product. Several students nominated this analogy as valuable in their weekly electronic reflections. And so the trap has been set for the last class session.On that morning, students will be divided into four person teams representing a cross-section of science certification areas. After a few preliminary bits of foolishness (e.g., "what element is sung immediately before and which is sung immediately after the element whose symbol is Sn?") the troops will receive the topic that is to be the focus of their lesson plan. They are to create an entire GULP format lesson based upon this supplied term. They are to also employ accommodations for English language learners and make sensible use of an educational technology. Actually, we may have to scratch the latter because it feels unrealistic. But in many ways it simulates what should transpire in the days and hours leading up to delivering a sample lesson to a roomful of strangers. Furthermore, it forces the participants to engage in debates about instructional design. Ideally, it will also induce them to engage in the spirit of collaboration that we believe is so central to the profession yet rarely demonstrated -- let alone practiced.

And that is our plan for now. Otherwise, I'm working on concepts that would be useful whether a person has allegiance to biology, chemistry or physics and have some evidence of a variety of student misconceptions. Currently, those topics are Oxygen, Energy Transformations and Conservation of Mass. Admittedly, it's not as clever as turning sheep fuzz into footwear. But at least I won't have to imagine how it all comes together.